Apple's folly

I have been thinking about Apple's dominant position in the (iOS) smartphone market for quite a few years, mostly in the context of how slow EU competition law enforcement is in regards with technology sectors. The last week or so, first with the EU Commission's investigation against the app store and Apple Pay and second with Apple's handling of the Hey email app made me conclude now is the time to put those thoughts in writing.

This post will be written exclusively from an EU law perspective. it will look into Apple's dominant position in iOS and app stores, as well some of its behaviours that may fall foul of the EU's competition law system, particularly Article 102 of the TFEU (abuse of dominant position). I will not get into some of the more nuanced or intricate details of EU competition law (ie, marketshare for example) as that would lead to very deep rabbit holes beyond the scope of this post.

1. Apple's dominant position on iOS

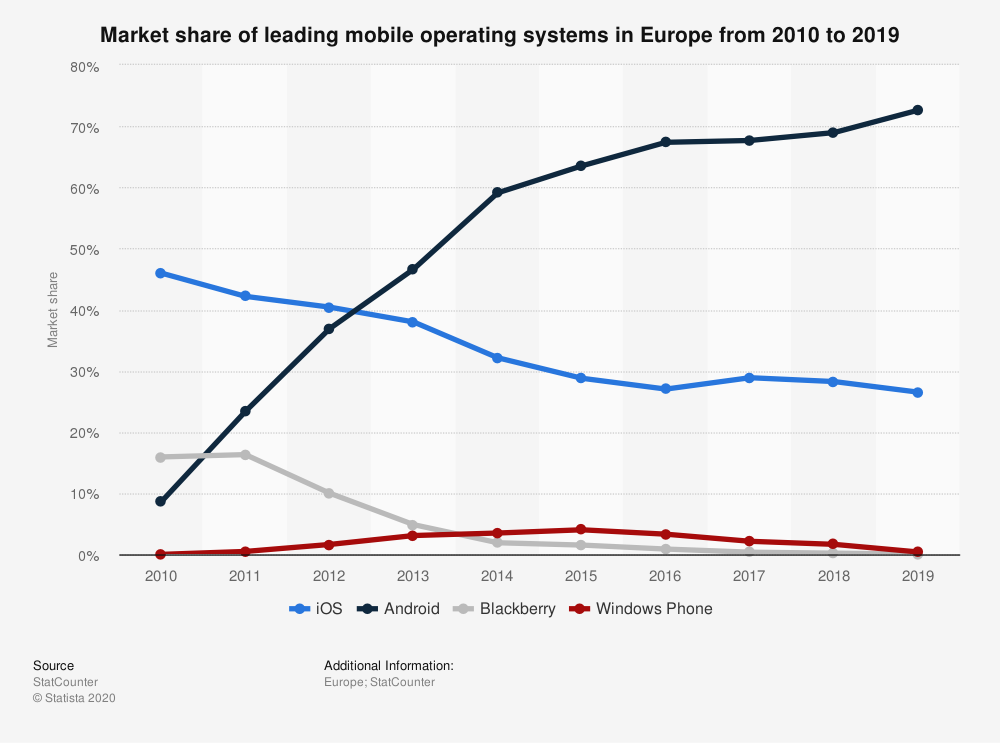

Any investigation into abuse of dominant position starts with determining if there is a dominant position to be abused at all. Without a dominant position, there can be no abuse, obviously. The smartphone sector provides us with some interesting battlelines to consider. On the one hand, we can consider the whole smartphone sector (iOS and Android these days) to be a single market and as such determining dominance depends on assessing the marketshare of both players. In most markets, Android has the majority of sales, so therefore it is pretty much impossible to argue Apple has a dominant position in the smartphone sector.

However, the concept of market depends on substitution of demand, ie can you replace product A with product B to serve a customer's needs? If the answer is yes, then both products compete in the same market.

As the European Commission (correctly) concluded in the Android case, iOS and Android are so different these days that effectively they represent separate markets without one fully replacing the other. This is evident when one looks at the low levels of customer transition between both systems. They have evolved into segregate markets.

This is partly the consequence of the moat strategy adopted by both Apple and (to a lesser extent) Google. Paradoxically, every attempt at building up the moat and increase the stickiness of each operating system further contributes to this segregation.

Therefore, if you are an iOS user, moving to Android implies giving up on iMessage, FaceTime, Apple Watch/Homepod management, Photos and iCloud/iCloud Drive. Crucially, all the investment you have made in paid apps is gone down the drain as well. In consequence, the more invested you are on one of the systems, the less likely it is you will be willing to move to the other. I am not argue that each of these were done with the intention of violating competition law, of course. It is just that increasing the stickiness of a platform ends up leading to market segregation.

My take since 2013 (and certainly today) is that from a competition law perspective, there is not a single smartphone market, but two separate ones: iOS and Android. Plus, in 2020 we cannot say the smartphone sector is new or evolving at great pace since we're down to two players.

For me, the conclusion is that Apple has a dominant position on iOS. Plus, it controls the *only* channel for software to be installed on iOS devices.

2. Apple's iOS app store dominant position

I'm sure Apple will fight tooth and nail the market definition above, but even if my view is wrong, when it comes down to the app store Apple won’t really be able to evade the conclusion it has a dominant position there.

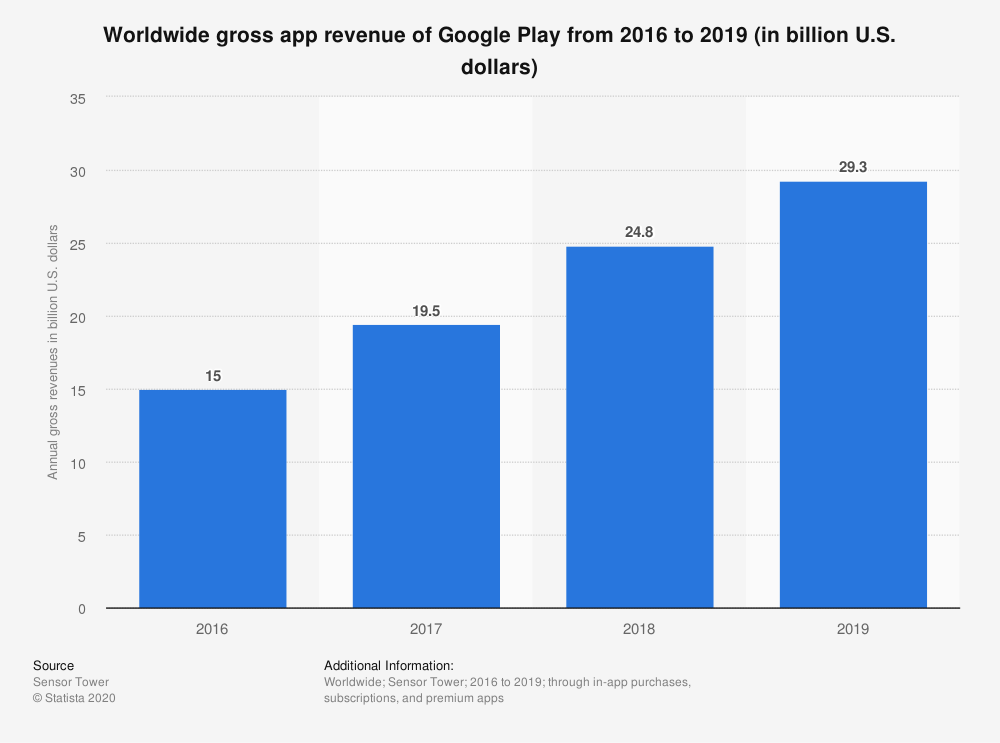

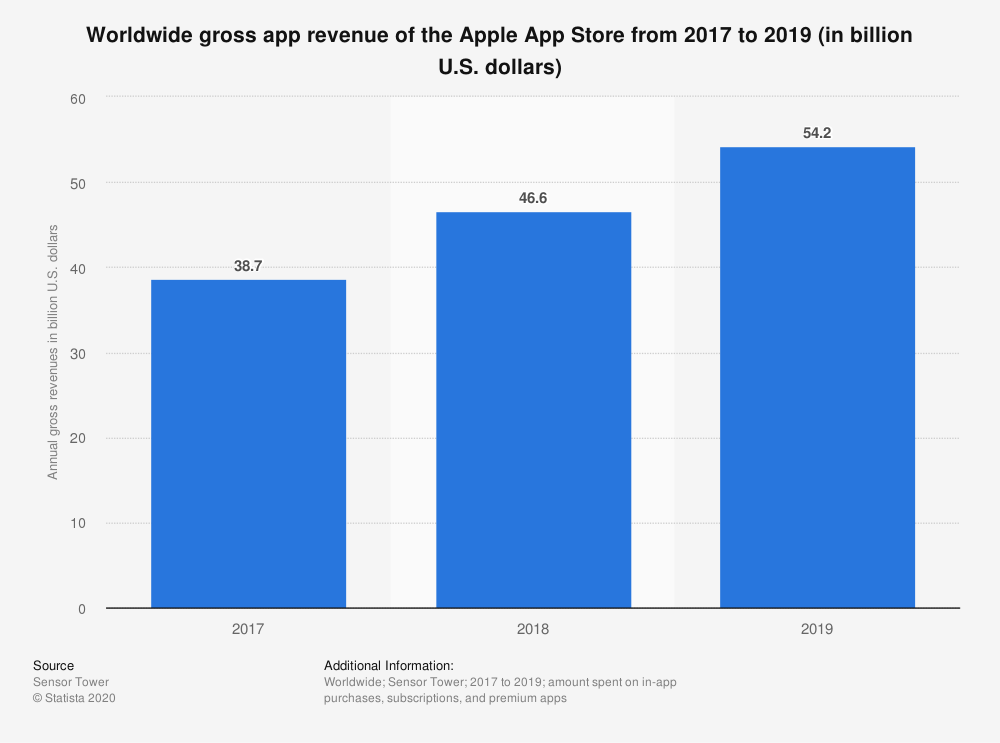

When it comes down to money spent on apps, the iOS app store is miles more valuable than Google Play. There is really no comparison, so if a developer wants to make money selling apps, most money to be made is on iOS and my guess is that this is consistent across markets.

Therefore, it is evident and unassailable that Apple's iOS app store has a dominant position in paid apps. Once more, the app store is the only way for paid or free apps to make it an iOS device. This makes the app store the sole gatekeeper for iOS software.

Having a dominant position is not problematic in itself for competition law. As long as that such position is not abused, that is.

3. The (abusive) behaviours

Looking at the behaviours is more difficult than simply the existence of a dominant position. They tend to be less well documented and thus harder to define and substantiate. Even so, there's a lot we already know how Apple behaves regarding its iOS app store.

Since its introduction that the split between Apple and developers has been 30/70, except for subscription apps from the second year onwards. Here's what was said back then:

“” — https://daringfireball.net/2008/03/iphone_sdk_impressions_and_questions

Back in 2008 that was a good deal. But the deal has remained unchanged for 12 years, even though the scale of the app store is very different today from what it was. I should add that competition law is a lot more forgiving on behaviours when a market is being set up than after it becomes established. It is fair to say that this is usually addressed in the context of agreements (Art 101 TFEU) and not abuse of dominant position, but the principle holds well here as well, especially bearing in mind the slowness of enforcement of competition rules in tech sectors.

As the app store is the only way to get software into iOS devices, any developer must comply with the rules set forth (exclusively) by Apple on a take it or leave it approach. And it is here that we need to look for abusive behaviours regarding the app store. Partly on the app stores, partly on specific decisions taken. This is one of the reasons why I refrained from writing about Apple in detail until Hey's case became public and the Commission started its own investigation.

Regarding payments, the rules are by themselves draconian: all payments need to be processed by Apple, where the latter takes the 30% cut and apps will be rejected (or taken out) if there is an attempt to circumvent the rules by clearly giving users the possibility of registering/paying on the web. This, in my view, will be one of the key bones of contention and where I think Apple is on very thin ice.

On Hey's case, it seems they did comply with the rules of the app store to the letter, but still Apple wants to take 30% of the $99 yearly subscription, or else the app will not remain on the store. On the face of it, that's a textbook abuse of a dominant position. What Apple is doing is forcing a developer to hand over 30% of its income made elsewhere.

The behaviour on Hey's case (publicly reiterated) is the folly mentioned in the headline. With a fresh competition infringement investigation on precisely this area, for Apple to accept a public fight about it is...interesting (in the British sense of the word). Plus, Apple has more to lose on the long run to keep the draconian stance on payments than by letting go and minimising the attack vectors for the Commission infringement proceedings.

What Hey's case has done, however, was to spring the lid wide open on more allegations of abusive behaviour. This is the tip of the proverbial iceberg as Ben Thompson wrote on one of his daily updates:

“”

And John Gruber as well:

“”

To me this sounds as a lot of competition law grievances waiting for the right opportunity to be aired. It is no surprise then Microsoft decided to troll Apple by publicly supporting the investigation of 'app stores' behaviours.

But Apple's questionable app store behaviours go beyond what was publicly discussed recently. For example, it bans any app with nudity or pornography, be it a magazine, a game, videos or apps for sex work. It also blocks electronic cigarette/e-vaping apps. At least in what concerns Member States of the Union, those would all be legal and yet Apple, as the sole gatekeeper of iOS software, determines it prefers to comply with other interests. For all the (correct) allegations of China exporting its world view and forcing companies elsewhere to toe the line, Apple has been doing something similar of exporting its own moral code across the world.

In addition, one could look to other iOS (but not app store) related behaviours. Apple Pay and access to NFC is one (which the Commission is rightly investigating) but also others such as the impossibility of changing default apps or, eventually, the use of private APIs by Apple's apps. I am not in a position at the moment to assess those in detail but, overall, they seem less problematic from a competition law point of view than the processing of payments.

4. Conclusion

On the face of the evidence available thus far (and yes, I'm aware of my own confirmation bias) my take is that Apple does have a dominant position (either by iOS being its own market or via the money spent on the app store) and that some of its behaviours are abusive in the context of EU competition. However, as always with these things, the devil will surely be on the details.

PS: I have not mentioned Astropad's 'sherlocking' accusation because they (mostly) conflate legitimate business decisions with competition law. Competition law exists to protect the market, not competitors and Astropad should have known it was in a risky position by making Luna only supporting iOS+macOS instead of other combinations of devices. Funny enough, they're now developing a Windows client after learning about 'the perils of limiting yourself to one platform provider.'